The green economy is one that results in improved human well-being and social equity, while significantly reducing environmental risks and ecological scarcities. Green economy is an economy or economic development model based on sustainable development and a knowledge of ecological economics.[1]

A feature distinguishing it from prior economic regimes is the direct valuation of natural capital and ecological services as having economic value (see The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity and Bank of Natural Capital) and a full cost accounting regime in which costs externalized onto society via ecosystems are reliably traced back to, and accounted for as liabilities of, the entity that does the harm or neglects an asset.[citation needed]

For an overview of the developments in international environment policy that led up to the UNEP Green Economy Report, see Runnals (2011).[2]

Green Sticker and ecolabel practices have emerged as consumer facing measurements of sustainability. Many industries are starting to adopting these standards as a viable way to promote their greening practices in a globalizing economy.

Contents[hide] |

[edit]"Green" economists and economics

"Green economics" is loosely defined as any theory of economics by which an economy is considered to be component of the ecosystem in which it resides (after Lynn Margulis). A holistic approach to the subject is typical, such that economic ideas are commingled with any number of other subjects, depending on the particular theorist. Proponents of feminism, postmodernism, the ecology movement, peace movement, Green politics, green anarchism and anti-globalization movement have used the term to describe very different ideas, all external to some equally ill-defined "mainstream"economics.[citation needed]

The use of the term is further ambiguated by the political distinction of Green parties which are formally organized and claim the capital-G "Green" term as a unique and distinguishing mark. It is thus preferable to refer to a loose school of "'green economists"' who generally advocate shifts towards a green economy, biomimicry and a fuller accounting for biodiversity. (see The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity especially for current authoritative international work towards these goals and Bank of Natural Capital for a layperson's presentation of these.)[citation needed]

Some economists view green economics as a branch or subfield of more established schools. For instance, as classical economics where the traditional land is generalized to natural capital and has some attributes in common with labor and physical capital (since natural capital assets like rivers directly substitute for man-made ones such as canals). Or, as Marxist economics with nature represented as a form of lumpen proletariat, an exploited base of non-human workers providing surplus value to the human economy. Or as a branch of neoclassical economics in which the price of lifefor developing vs. developed nations is held steady at a ratio reflecting a balance of power and that of non-human life is very low.[citation needed]

An increasing consensus around the ideas of natural capital and full cost accounting could blur distinctions between the schools and redefine them all as variations of "green economics". As of 2010 the Bretton Woods institutions (notably the World Bank[3] and International Monetary Fund (via its "Green Fund" initiative) responsible for global monetary policy have stated a clear intention to move towards biodiversity valuation and a more official and universal biodiversity finance.[citation needed] Taking these into account targeting not less but radically zero emission and waste is what is promoted by the Zero Emissions Research and Initiatives.[citation needed]

[edit]Definition of a green economy

Karl Burkart defines a green economy as based on six main sectors:[4]

- Renewable energy (solar, wind, geothermal, marine including wave, biogas, and fuel cell)

- Green buildings (green retrofits for energy and water efficiency, residential and commercial assessment; green products and materials, and LEED construction)

- Clean transportation (alternative fuels, public transit, hybrid and electric vehicles, carsharing and carpooling programs)

- Water management (Water reclamation, greywater and rainwater systems, low-water landscaping, water purification, stormwater management)

- Waste management (recycling, municipal solid waste salvage, brownfield land remediation, Superfund cleanup, sustainable packaging)

- Land management (organic agriculture, habitat conservation and restoration; urban forestry and parks, reforestation and afforestation and soil stabilization)

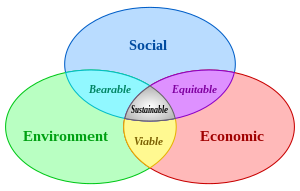

The Global Citizens Center, led by Kevin Danaher, defines green economy differently from the use of pricing mechanisms for protecting nature, by using the terms of a "triple bottom line," an economy concerned with being:[5]

- Environmentally sustainable, based on the belief that our biosphere is a closed system with finite resources and a limited capacity for self-regulation and self-renewal. We depend on the earth’s natural resources, and therefore we must create an economic system that respects the integrity of ecosystems and ensures the resilience of life supporting systems.

- Socially just, based on the belief that culture and human dignity are precious resources that, like our natural resources, require responsible stewardship to avoid their depletion. We must create a vibrant economic system that ensures all people have access to a decent standard of living and full opportunities for personal and social development.

- Locally rooted, based on the belief that an authentic connection to place is the essential pre-condition to sustainability and justice. The Green Economy is a global aggregate of individual communities meeting the needs of its citizens through the responsible, local production and exchange of goods and services.

The Global Green Economy Index,[6] published annually by consultancy Dual Citizen Inc., measures and ranks the perception and performance of 27 national green economies. This index looks at 4 primary dimensions defining a national green economy as follows:

- Leadership and the extent to which national leaders are champions for green issues on the local and international stage

- Domestic policies and the success of policy frameworks to successfully promote renewable energy and green growth in home market

- Cleantech Investment and the perceived opportunities and cleantech investment climate in each country

- Green tourism and the level of commitment to promoting sustainable tourism through government[citation needed]

You can take part in a student project to define the Green Economy in the run-up to the Rio+20 [1] conference on the Green Economist website [2].

[edit]Other issues

Green economy includes green energy generation based on renewable energy to substitute for fossil fuels and energy conservation for efficient energy use.[citation needed]

Because the market failure related to environmental and climate protection as a result of external costs, high future commercial rates and associated high initial costs for research, development, and marketing of green energy sources and green products prevents firms from being voluntarily interested in reducing environment-unfriendly activities (Reinhardt, 1999; King and Lenox, 2002; Wagner, 203; Wagner, et al., 2005), the green economy may need government subsidies as market incentives to motivate firms to invest and produce green products and services. The German Renewable Energy Act, legislations of many other member states of the European Union and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, all provide such market incentives.[citation needed]

[edit]Criticisms

A number of organisations and individuals have criticised aspects of the 'Green Economy', particularly the mainstream conceptions of it based on using price mechanisms to protect nature, arguing that this will extend corporate control into new areas from forestry to water. The research organisation ETC Group argues that the corporate emphasis on bio-economy "will spur even greater convergence of corporate power and unleash the most massive resource grab in more than 500 years."[7] Venezuelan professor Edgardo Lander says that the UNEP's report, Towards a Green Economy,[8] while well-intentioned "ignores the fact that the capacity of existing political systems to establish regulations and restrictions to the free operation of the markets – even when a large majority of the population call for them – is seriously limited by the political and financial power of the corporations." [9] Ulrich Hoffmann, in a paper for UNCTAD also says that the focus on Green Economy and "green growth" in particular, "based on an evolutionary (and often reductionist) approach will not be sufficient to cope with the complexities of climate change" and "may rather give much false hope and excuses to do nothing really fundamental that can bring about a U-turn of global greenhouse gas emissions.[10] Clive Spash, an ecological economist, has criticised the use of economic growth to address environmental losses,[11] and argued that the Green Economy, as advocated by the UN, is not a new approach at all and is actually a diversion from the real drivers of environmental crisis.[12] He has also criticised the UN's project on the economics of ecosystems and biodiversity (TEEB),[13] and the basis for valuing ecosystems services in monetary terms.[14]

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar